Coastal setbacks, buffers or managed retreat stipulate areas or zones along the coastline within which all or certain types of![]() development are prohibited. This provides a buffer between coastal development and areas likely to be impacted by sea level rise, increased storm surges and beach erosion. Coastal setbacks are established based on historic erosion rates and/or extreme water levels and projected changes.

development are prohibited. This provides a buffer between coastal development and areas likely to be impacted by sea level rise, increased storm surges and beach erosion. Coastal setbacks are established based on historic erosion rates and/or extreme water levels and projected changes.

Types of coastal setbacks include:

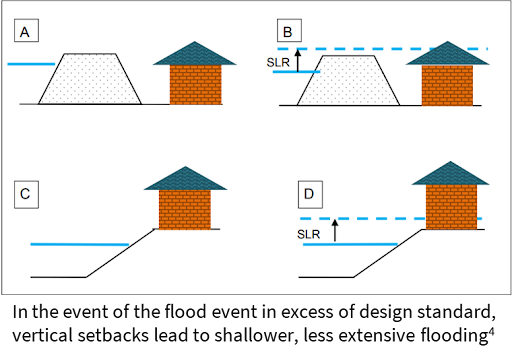

- Elevation setback to cope with coastal flooding

- Lateral setback to cope with coastal erosion

![]()

![]()

As it is a land use planning mechanism only, development of coastal setback does not guarantee that the coast will be shielded from strong storms and the associated coastal flooding and erosion. Thus, it is often applied in combination with physical measures such as artificial sand dune rehabilitation, beach nourishment, mangrove reforestation or coastal protection. Outreach is critical for landowners to understand the risk in higher risk areas and compliance and enforcement are critical for setback zones and rules to be effective.

Coastal retreat or managed retreat can range from low cost (if setbacks are implemented before an area is developed) to high cost (if major relocation of infrastructure is required). Whilst providing cost estimates is difficult given the broad range of influencing factors across the Pacific, the below table outlines the key components that should be taken into account when estimating a coastal setback/managed retreat budget for a specific location.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

Coastal setbacks or managed retreat is compared to constructing hard infrastructure such as dikes and seawalls. Comparing the two approaches shows that”:

Hard infrastructure can be effective in stabilizing the shoreline but can destabilize the beach and other ecosystem services provided by the coast.

- Construction of dikes and seawalls further degrade natural habitats by exacerbating erosion and

impacting the seabed and neighboring coastline.

impacting the seabed and neighboring coastline. - A buffer is a more cost-effective adaptation option to protect communities compared to last line of defense structures (seawalls).

- Unlike hard structures, setbacks help to maintain the natural appearance of the coastline and preserve natural shoreline dynamics.

- Coastal setback can provide multiple-use opportunities (e.g. recreational and tourism as well as environmental protection).

- The use of vertical setbacks can lead to shallower, less extreme flooding compared to the use of hard infrastructure (see Figure).

- -

Coastal Change in the Pacific Islands, Volume Two: A Guide to Support Community Decision-Making on Coastal Erosion and Flooding Issues. See https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Coastal%20Change%20Toolkit%20_V2_Final.pdf

- -

Technologies for Climate Change Adaptation - Coastal Erosion and Flooding. See https://www.researchgate.net/publication/216584246_Technologies_for_Climate_Change_Adaptation_-_Coastal_Erosion_and_Flooding

- -

Coastal Change in the Pacific Islands, Volume One: A Guide to Support Community Understanding of Coastal Erosion and Flooding Issues. See https://reliefweb.int/report/world/coastal-change-pacific-islands

- -

Responding to the challenges of climate change in the Pacific Islands: management and technological imperatives. See https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237092359_Responding_to_the_challenges_of_climate_change_in_the_Pacific_Islands_Management_and_technological_imperatives

- -

UN Climate Technology Centre & Network. See https://www.ctc-n.org/technologies/coastal-setbacks

- -

1. Coastal Change in the Pacific Islands, Volume One: A Guide to Support Community Understanding of Coastal Erosion and Flooding Issues. See https://reliefweb.int/report/world/coastal-change-pacific-island

- -

2,3,4. Technologies for Climate Change Adaptation – Coastal Erosion and Flooding. See https://www.researchgate.net/publication/216584246_Technologies_for_Climate_Change_Adaptation_-_Coastal_Erosion_and_Flooding

Case study

The Coastline of Future Pacific

Tonga’s Lifuka Island was struck by earthquake in May 2006, subsiding the land by 23 cm. Lifuka was chosen as part of a unique regional effort to understand how vulnerable Pacific Island communities can adapt to the impacts of rising sea levels. The Government of Tonga with assistance from the Australian-funded Pacific Adaptation Strategy Assistance Program recruited scientists to work closely with the Lifuka community to determine adaptation options. The community considered three adaptation options to address flooding and coastal erosion:

- Beach nourishment

- Managed retreat (i.e. planned migration inland)

- Construction of seawall.

Before the project, the community was convinced that building a seawall was the best option. Small efforts using sandbags for coastal protection were already in place but were regularly eroded by storm surges. After community consultation about the pros and cons of each option, managed retreat was identified as the best option to protect the community.

The managed retreat could include government incentives to help people move out of hazard-prone areas. In addition, there would be a need to support with people who don’t have land inland, and for discussions among clans to determine how people could move back to their familial lands. Managed retreat on Lifuka Island is now ensuring long-term safety of community members, buildings, and infrastructure from coastal change (e.g. flooding and erosion).

The following video provides further detail on this case study: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VJnEvyg5aj0

Reference: Assessing vulnerability and adaptation to sea-level rise: Lifuka Island Ha’apai, Tonga, https://tonga-data.sprep.org/system/files/Lifuka_%20Final%20report_%20Rising%20Oceans%20Changing%20Lives.pdf