Adaptive forest management is intended to enhance the functionality of forests and productivity of commercial forest ventures under the multiple pressures of climate change. Climate change impacts can cause significant alteration of the growing conditions through increasing of extreme weather events, changing hydrological regimes and increasing prevalence and spread of disease. The intent of integrating a diversity of tree species into managed forests is to increase the adaptive capacity of those forests to resist and recover from the impacts of climate change.

Natural or adaptively managed forests contain a diversity of woody species. By integrating a range of trees with different functional types into a forest, resources such as light, water and nutrients can be spatially and temporally used by different species at different times, leading to an increase in resilience. Managed forests with low diversity (e.g. plantations) are ultimately more vulnerable to changing conditions with a lower ranges of tolerance to any impacts, increasing the likelihood of extensive damage to forest function leading to large scale and sometimes irreversible shifts in the condition of the forest.

Possible adaptive forest management interventions include:

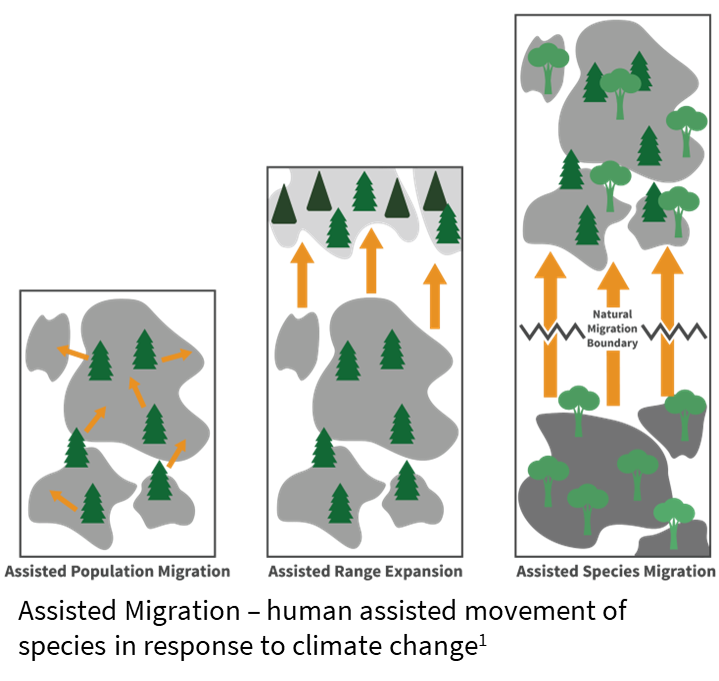

- Assisted introduction of tree species: This intervention seeks to mimic or accelerate the expected

transformational processes that would occur naturally as a forest adapts to climate impacts. Assisted introduction of species is a generic term that includes a variety of potential actions. These include: 1) Assisted population migration (also assisted genetic migration or assisted gene flow) which involves moving seed sources or populations to new locations within the historical species range; 2) Assisted range expansion involving moving seed sources or populations from their current range to suitable areas just beyond the historical species range; 3) Assisted species migration (also species rescue, managed relocation, or assisted long-distance migration) – moving seed sources or populations to a location far outside the historical species range , beyond locations accessible by natural dispersal.

transformational processes that would occur naturally as a forest adapts to climate impacts. Assisted introduction of species is a generic term that includes a variety of potential actions. These include: 1) Assisted population migration (also assisted genetic migration or assisted gene flow) which involves moving seed sources or populations to new locations within the historical species range; 2) Assisted range expansion involving moving seed sources or populations from their current range to suitable areas just beyond the historical species range; 3) Assisted species migration (also species rescue, managed relocation, or assisted long-distance migration) – moving seed sources or populations to a location far outside the historical species range , beyond locations accessible by natural dispersal.

- Active restoration of key forest functions: Whilst active restoration of degraded forests has been a significant part of conservation planning globally, assisted or targeted restoration to assist managed forests adapt to climate change is an emerging field. However, efforts have been made to target the components of forests vulnerable to climate change like riparian areas (vulnerable to increased river flow velocity and erosivity) and forest edges (vulnerable to physical damage by extreme events).

- Ecosystem based approaches to management: There is a growing body of evidence that shows natural disturbance-based forest management is effective in mitigating the effects of large-scale pressures like climate change. Natural disturbances are a driving force in creating and maintaining diversity in ecosystems including structural diversity, genetic diversity, biodiversity and ecological functions. Actively managing forests by mimicking natural disturbance regimes instills a diversity of species and functions that increases the adaptive capacity of a forest.

Adaptive forest management implementation would be low to medium depending on the size of forest being managed (e.g. from community cooperative to large scale commercial forestry). Whilst providing cost estimates is difficult given the broad range of influencing factors across the Pacific, the below table outlines the key components that should be taken into account when estimating an adaptive forest management project budget for a specific location.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

Adaptative forest management approach of forest management is compared against conventional approaches of maximising sustained forest yields.

- Conventional approach to forest management of maximising forest yield disregard ecological sustainability of forest while adaptive forest management increases the capacity of forest (natural/manmade) including commercial plantations.

- Conventional approach focuses on intensive wood production and no other function of forests while adaptive forest management looks at diversity of functions provided by forest like cultural, economic, environmental etc.

- The sole focus on focusing on yields/logging has negative impacts on biodiversity, nutrients, water production, altering fire regimes etc. while adaptive management approach focuses on a diversity of woody species having a range of trees with different functional types distributed spatially and temporally throughout the forest.

- Conventional approaches are not resilient to climate change shocks while adaptive management approaches are flexible to the climatic impacts and maintains the diversity of forest.

- -

Natural Disturbance-Based Forest Management: Moving Beyond Retention and Continuous-Cover Forestry. See https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2021.629020/full

- -

Forest adaptation to climate change—is non-management an option?. See https://annforsci.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1007/s13595-019-0827-x

- -

Assisted Migration. See https://www.fs.usda.gov/ccrc/topics/assisted-migration

- -

A Review on Benefits and Disadvantages of Tree Diversity. See https://benthamopen.com/contents/pdf/TOFSCIJ/TOFSCIJ-1-24.pdf

- -

Diversifying Forest Landscape Management—A Case Study of a Shift from Native Forest Logging to Plantations in Australian Wet Forests. See https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359157519_Diversifying_Forest_Landscape_Management-A_Case_Study_of_a_Shift_from_Native_Forest_Logging_to_Plantations_in_Australian_Wet_Forests

- -

1. Assisted Migration. See https://www.fs.usda.gov/ccrc/topics/assisted-migration

Case study

Sustainable Forest Management practice

Over the past few decades, Australia has been adopting a Sustainable Forest Management Approach to managing its native and production forests. This approach recognises that forests are complex ecosystems that provide a wide array of environmental and socioeconomic benefits and services. The aim of Sustainable Forest Management is therefore to maintain the broad range of forest values in perpetuity.

In Australia a comprehensive framework has been established to drive the adoption of Sustainable Forest Management practices across the country. This includes:

- A national policy framework – the country’s 1992 National Forest Policy Statement (NFPS) promotes conservation and sustainable management of forests.

- Australia's Sustainable Forest Management Framework of Criteria and Indicators 2008 and regular reporting – internationally recognised framework for sustainable forest management applied to Australia’s forests. Based on the Framework, every five years an Australia State of the Forest Report is published.

- Regional Forest Agreements (RFAs) – these 20-year agreements underpin regional approaches to balancing conservation and production from native forests.

- Forest certification – independent third-party forest certification to forest management standards is undertaken for most of Australia’s production forests.

Reference: Australia’s Sustainable Forest Management, https://www.awe.gov.au/agriculture-land/forestry/australias-forests/forest-mgnt